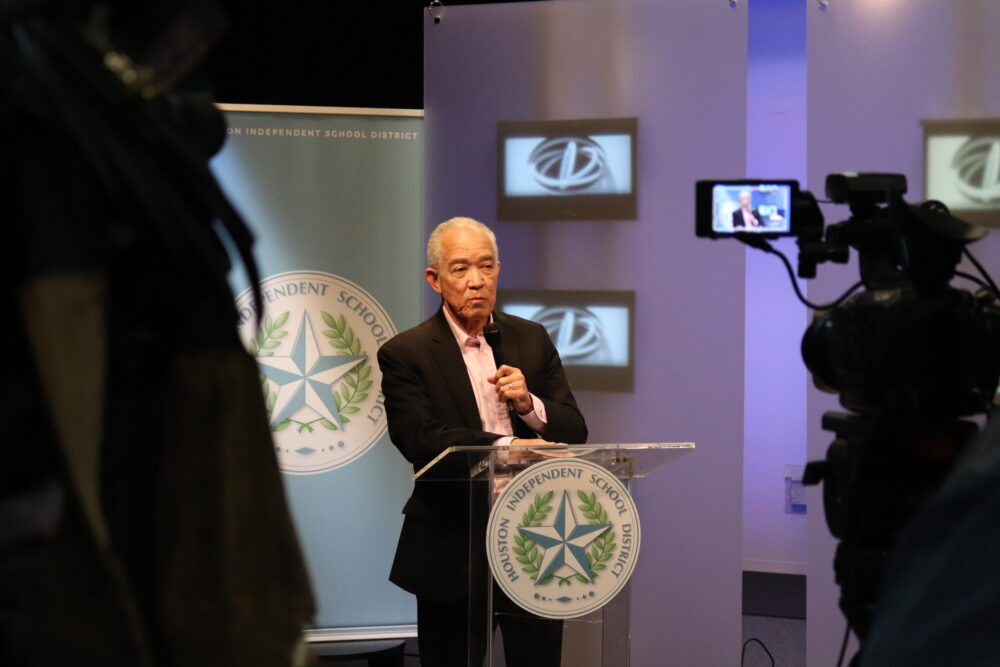

Dominic Anthony Walsh/Houston Public Media

More Houston ISD campuses will face sweeping reforms next school year, as state-appointed superintendent Mike Miles expands his so-called New Education System (NES) in an effort to turn around schools that have struggled to meet state standards.

“The accountability rating shows that they have declining achievement, and we need to arrest that decline,” Miles said in an interview with Houston Public Media prior to the announcement. “They need additional supports. They need to change what they’re doing.”

Starting next year, more than 110 Houston ISD schools will fall under the NES umbrella. The additions include Westbury and Sharpstown high schools, along with 24 elementary and middle schools. Campus principals at another 24 schools, including Austin High School and about two dozen elementary and middle schools, will have the option to apply for the reform program after consulting with staffers and families.

MORE: Dominic Anthony Walsh discusses this story on Houston Matters

The NES expansion continues Houston ISD’s shift away from a decentralized model, where most campuses for decades enjoyed significant autonomy over staffing, schedules and instruction. Next year, about 40% of the schools in the district will have centralized schedules with longer school days, a district-approved model of classroom instruction, tightly scripted lessons followed by quizzes every class, as well as higher salaries for educators and a staffing model that excludes librarians. Those changes come as the district’s existing support programs for low-income families shift focus.

A full list of the additional NES schools can be viewed here.

Students who are already at NES schools have mixed feelings about the changes

The Texas Education Agency appointed Mike Miles to lead the state’s largest public school system in June 2023, and he immediately announced reforms to 28 schools. By the end of the summer, an additional 57 campus principals opted in.

At Wheatley and nearby Kashmere High, which also struggled to meet standards, students described a breakneck speed of instruction and heavier-than-normal workload.

“We have no fun, working 24/7, hard work every day,” said Wheatley High senior Rodney Deshar in December. “Work, work, work, work, work — every day, every day.”

Some students, like Kashmere High junior Anthony Connor, praised the improved discipline and decreased disruptions.

“I feel definitely like more of a student this year than last year,” Conner said in August. “Because last year, I was just doing whatever I wanted to do.”

Other students feel the administration is overemphasizing test-based subjects and discipline at the expense of students’ emotional and social wellbeing.

Teacher turnover is expected to remain higher than normal as reforms expand

As Houston Public Media first reported last week, the number of HISD teachers who resigned from August through early January nearly doubled compared to the previous two school years. Union president Jackie Anderson with the Houston Federation of Teachers blamed a “culture of fear and intimidation.”

“What we’re doing with the staffing model is not so much looking at retention or recruitment,” Miles said. “We’re looking at making sure that kids have 180-some student-teacher contact days of high-quality instruction.”

Over the summer of 2023, educators at each of the first 28 NES schools had to reapply for their jobs. At each of the 26 new NES schools, all educators will have to go through a “proficiency screening” to retain their positions.

“If they want to stay, we will look at a teacher’s spot observations, we will look at their achievement data mid-year, we’ll look at their principal’s recommendation, and we’ll use an algorithm to assess where their proficiency level is,” Miles said. “If they’re proficient or higher, they get to stay.”

Through a public records request, Houston Public Media obtained a rubric outlining interview procedures for teachers who sought NES jobs last summer.

One hypothetical interview question focuses on two schools with “similar demographics and numbers of students.” At one school, student behavior is “out of control.” Applicants are asked to explain possible reasons why the other school didn’t have this problem.

Out of the six preferred responses, five point to a culture of “high performance” or “high expectations,” while only one references “building relationships.”

Ruth Kravetz, retired HISD educator and cofounder of Community Voices for Public Education, saw the document as representative of her broader critique of the NES system.

“First, I would build relationships with kids because kids who have less access to resources — all human beings, really — need to build trust,” Kravetz said. “The way to improve students’ capacity to learn is to treat children like human beings, which I think is the biggest problem with this factory model that he’s promoting.”

Miles argued discipline has improved dramatically across the current NES campuses.

“Maybe enforcing common sense discipline — while you’re having teachers build relationships — maybe that is the way to go,” Miles said. “It seems like it is.”

Beyond the “high-performance” approach, NES schools also feature tightly scripted, centrally created curricula. As Duncan Klussman with UH’s College of Education explained, teachers who value a higher degree of autonomy over classroom instruction might not be a good fit.

“It’ll take a while for individuals coming in to understand that they’re going to be given their curriculum and their lesson and not really have any autonomy over that,” Klussman said. “If they’re comfortable with that, that’s fine, but you probably have a lot of folks in HISD who are not comfortable with that.”

Existing support services for HISD families have declined or shifted focus under state-appointed administration

Before the takeover, Houston ISD leaned into a “community schools” model through the expansion of wraparound services, which the district described as “a comprehensive approach to student support that aims to develop the physical, mental, cognitive, and social-emotional development of students.” There were about 250 wraparound support specialists across the district as of early January, according to HISD’s public information office. The department designed campus-specific programs that fulfilled basic unmet needs, like food pantries and clothing closets — until this month. Wraparound specialists will now focus on reducing chronic student absences and dropouts.

A document obtained by Houston Public Media outlines the foundational shift. Before January, the department’s top goals included “increase accessibility to food pantries” and “deliver targeted support based on identified needs.” Now, wraparound specialists’ top priorities are a 2% reduction in the number of students with ten or more absences as well as a 1% decrease in the number of high school dropouts.

Kravetz with CVPE argued the changes amount to “essentially dismantling wraparound services and turning it into something else.” Kravetz and other critics are concerned about the new priorities derailing the focus of the department.

“It looks like we’re now truancy officers,” said one HISD wraparound specialist who requested anonymity due to fear of retaliation.

Wraparound specialists are now encouraged to “refer families to Sunrise Centers to remove barriers preventing students from attending school.” In addition to the Central Office administrative building, there are seven newly opened Sunrise Center locations across the district where the district says families can access a range of supports like before and after-school care, mental health services, tutoring and school supplies.

Savant Moore is the newly sworn-in trustee for Houston ISD’s District 2 in Northeast Houston, where many schools faced changes under the first round of NES reforms.

“I live in Fifth Ward,” Moore said just after he was sworn in this month. “We do live in a food desert. How many grocery stores are there? We also live in a broadband desert. These children don’t have Wi-Fi access to do their work. There’s also socio-economic issues. People don’t have that income.”

He urged the administration to ramp up wraparound services at each campus.

“I know there’s a Sunrise Center, but there’s a transportation issue,” Moore said. “They may not be able to get to the Sunrise Center, so we need to reach them at the school.”

Miles said the administration is in the process of “redefining the role” of wraparound specialist and attempting to measure its impact.

“We’re not here just for food access, as important as that is,” Miles said. “It’s not mutually exclusive. They’re working on food access. They’re working on clothing. They’re working on getting kids to the Sunrise Center.”

Erin Baumgartner is director of the Houston Education Research Consortium at Rice University’s Kinder Institute. She said HERC is set to launch a research project in coordination with Houston ISD to determine if Sunrise Centers are “in the right places where we need them, if students and families are accessing them, and how they’re feeling about whether their needs are being met.”

“HISD leaned on a lot of research from HERC and Kinder Institute in thinking about where to place those centers, and so we said ‘Okay, that’s great, but now you need to know if that was the right thing,'” Baumgartner said. “The idea is getting the district that information as soon as possible so they can use it to tweak things, adjust, course correct, and better serve students.”

The shift in focus for wraparound specialists came on the heels of large cuts to the number of workers in the Central Office’s homeless department. According to information obtained by Houston Public Media, there were 40 staffers in HISD’s Homeless Office in January 2023. Now, there are 12.

What’s next?

The state takeover happened because Wheatley High School in Houston’s Fifth Ward failed to meet state standards for several years in a row.

The accountability system — which awards campuses and districts an A through F score based on student test results and post-graduation preparedness — is a moving target. The Texas Education Agency is currently defending its revamped, more stringent system in court against a challenge from more than 100 other school districts. If implemented, more than 110 HISD campuses would have failed to meet state standards last school year compared to less than 10 the year before, according to Miles. Only 35 HISD campuses would have earned an A, 58 would have received a B, and 52 would have scraped by with a C.

Each of the 26 schools added in this new round of NES expansion would have received F or D ratings last year, while the 24 opt-in campuses would have earned D grades. Miles said the NES system will eventually expand to cover about 150 schools — more than half the district — by the 2026-27 academic year. In order for the takeover to end, all Houston ISD schools must consistently meet state standards.

More than ending the takeover, the NES expansion is part of an ambitious plan to significantly raise student test scores and to cut the achievement gap — between Black and Latino students and their white peers — almost in half over the next five years.

Miles said the gap might be impossible to close completely through school reform alone, but in his view, it won’t narrow without “raising expectations.”

“Education is not just about what’s happening in schools,” he added. “One of the things you’ll see in the NES model is that we believe there’s a couple other things that are really important that most schools don’t do. Most schools don’t try to expand experiences for kids beyond the elective. Most schools also don’t focus on your 2035 competencies like critical thinking, information literacy and problem-solving.”

Asked if the gap can ever be closed, Miles said, “I don’t know.”

“Can we mirror in public education what wealthy people or people with means can do for their kids outside of the walls of these schools?” he asked. “No. We can come close, but it’s just too many resources. So you asked me, can the gap ever be closed? I don’t know. It’s not all up to us.”

Every Houston ISD campus can expect to see changes regardless of their state accountability rating by the 2025-26 school year, when the district plans to implement a pay-for-performance system that ties educator pay to student test scores and classroom evaluations rather than years of experience.

Even though Houston ISD continues to see declining enrollment, Miles promised that campus closures will remain off the table until after the 2024-25 school year.

“One of the challenges I have — and I think communities would properly complain about — is if we close a school when we have not done a good job of helping the school improve academically or haven’t improved the school’s behavior,” he said. “That doesn’t feel right … so we’re going to be slow to close those schools.”